I recently made a trek to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) with a couple of friends for a day of culture and artistic inspiration. My ulterior motive for our little excursion was to see a special video installation of Merce Cunningham’s work. The exhibit is called Merce Cunningham, Clouds and Screens and is on display through March 31, 2019.

Last week’s post focused on Merce Cunningham’s background and artistic legacy. Today I will tell you about the exhibit at LACMA.

Merce Cunningham, Clouds and Screens consisted of two installations and two video projections. It was housed on the first floor of the Broad Contemporary Art Museum building at LACMA.

In the foyer was a work called Silver Clouds by Andy Warhol and Billy Klüver . The label explained that the silver mylar “pillows” were originally a work exhibited by Andy Warhol in 1966. Cunningham approached Warhol about adapting the work as the scenic elements of his dance, Rainforest (1968). It was a fun, interactive way to begin to experience the exhibit.

Next, we spent a few minutes watching a piece called Changeling (1957) that was being projected in an adjacent gallery. It was a great illustration of the way that Cunningham would use random chance to create movements. The way that movements of the head, torso, arms, and legs were combined randomly created very complex and unnatural feeling movements.

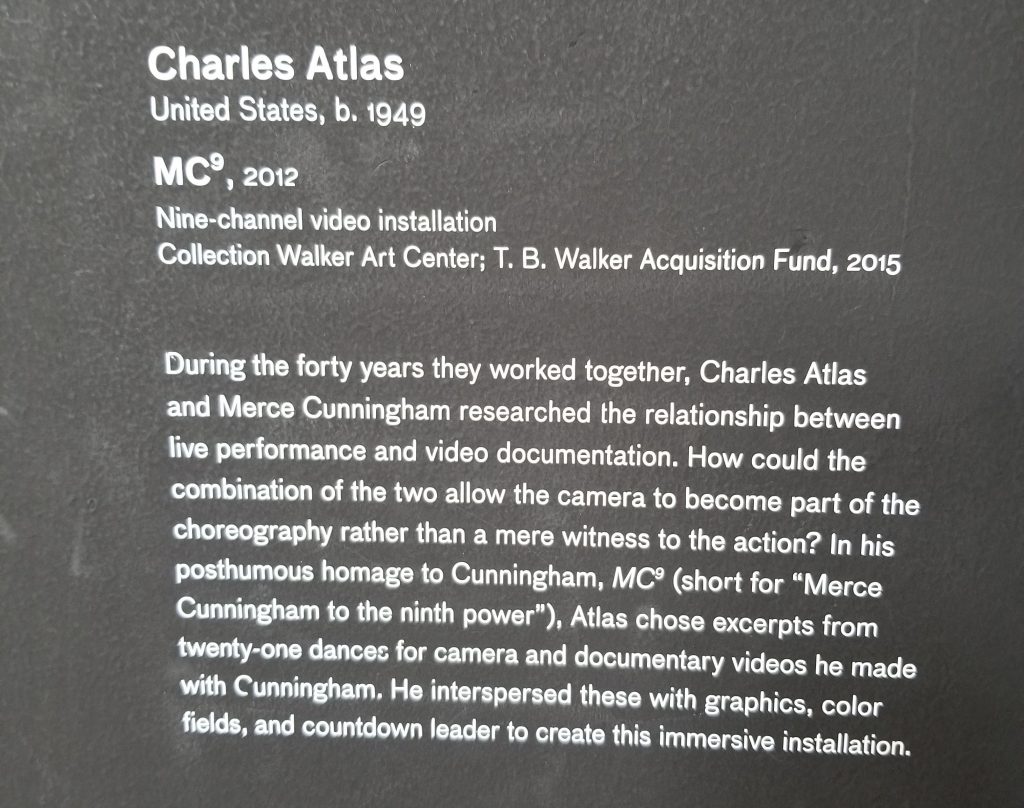

After watching Changeling briefly, we were ready to enter the main exhibit, Charles Atlas’s installation, MC⁹ (2012). Well, as ready as we were going to be. It was a fantastic sensory immersion. There was so much to look at. It took a while to realize that there wasn’t any specific order or right way to experience it. One great aspect of the installation was that if there was something that you missed or wanted to spend more time watching, it would likely be coming up on another screen in the gallery sometime soon.

The installation consisted of a black box room with nine 8’x12’ double-sided projection screens (get it, nine screens, wink, wink) at various heights and on various angles throughout the space. Interspersed among the projection screens were a number of smallish (36” to 48”) monitors. The screens and monitors showed seemingly random clips of various Merce Cunningham Dance Company (MCDC) performances and Cunningham himself performing. A clip may be on one or both sides of one of the large screens, on a small monitor next to it, and on another screen on the other side of the exhibit simultaneously. One of the gallery attendants who I spoke to said that the entire piece is a loop that runs for more than an hour.

We spent nearly an hour walking around the space, experiencing the exhibit from different perspectives. Eventually, I let go of my obsessive desire to try to determine some sort of pattern in the way that the clips were shown on various screens at certain times. I’m not convinced that it was completely random, but whatever pattern existed was complicated enough that it would have taken more time than I was willing to devote to deciphering it. It was enough to step back and just let the experience happen.

In general, I find the concept of random chance in the creation of artwork fascinating. It is one of those things that does not discard technique and virtuosity. Randomness does not mean that the elements are not carefully considered and created. In some ways, I would think that the component elements of a work would need to be more precisely crafted. Cunningham was certainly a pioneer in applying this methodology to creating dance. The only contemporary choreographer who I am aware of who is currently working in a similar milieu is Bill T. Jones. I hope that there are others.