I recently made a trek to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) with a couple of friends for a day of culture and artistic inspiration. My ulterior motive for our little excursion was to see a special video installation of Merce Cunningham’s work. The exhibit is called Merce Cunningham, Clouds and Screens and is on display through March 31, 2019.

I find Merce Cunningham fascinating, so this will be a two-part post. Today will be some background about him and next week’s post will be about the exhibit.

Merce Cunningham (1919-2009) was a mid-20th century, American, modern dance pioneer.

Growing up, Cunningham studied tap dancing. This medium emphasizes precise musical timing and rhythm, which would become foundations of his technique. His first professional dance experience was with the Martha Graham company. He danced with Graham for six years (1939-1945) before leaving to establish his own dance company, Merce Cunningham Dance Company (MCDC).

A prolific creator, over the course of his 60+ year career, Cunningham created 190-200 dances and 700-800 events. A Cunningham dance is a stand-alone piece of choreography, which could be recreated. By contrast, an event is defined as a site/time specific performance. Mindful of his artistic legacy, he established the Merce Cunningham Trust in 2000 to hold and administer the rights to his works after his death.

His work is known for innovative use of collaboration,

chance, perspective, and technology.

Collaboration

Cunningham’s most enduring collaboration was with his partner, composer John Cage. The two presented their first collaborative performance in 1944 and continued to work together until Cage’s death in 1992. As collaborators, they provocatively asserted that dance and music should not intentionally be coordinated. This is a radical departure from dance convention.

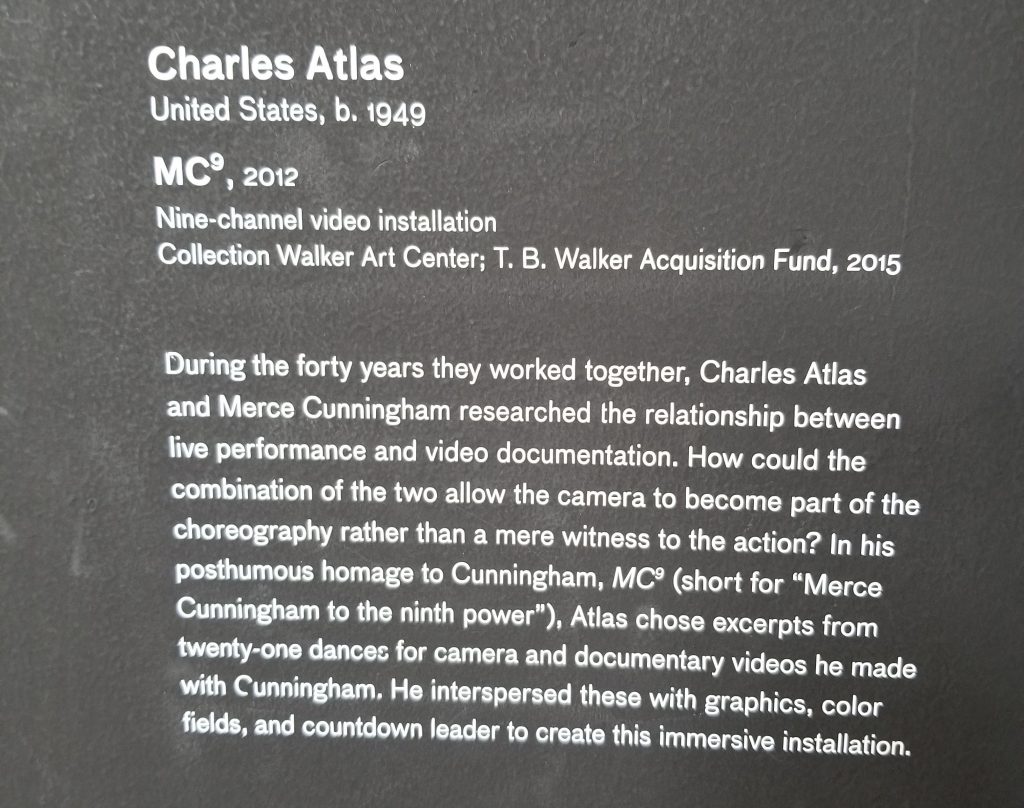

Cunningham’s collaborations with visual artists included Robert

Rauchenberg (MCDC resident designer 1954-1964), Jasper Johns (MCDC artistic

advisor 1967-1980), Rei Kawakubo, Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, and filmmaker Charles

Atlas.

Chance

To me this is the most fascinating and innovative facet of Cunningham’s work. Cunningham and Cage became interested in the concept of chance in the 1950’s when a translation of the ancient Chinese text, I Ching was published in the U.S. They began using stochastic operation (random chance) to determine musical composition and dance movements.

Stochastic operation was employed by Cunningham in a number

of different ways. It could be used to

create steps, to determine the sequence of steps, and/or even the number/composition

of performers.

In order to create steps, Cunningham divided the body into

parts – head, arms, torso, legs. He

would generate lists of all possible movements for each part, then use random

chance to determine the movement of each part in order to create a step. This created choreography that was often

exceedingly difficult to execute.

Often sequences and dancers would not be determined until just before the performance. Further, this was all done without regard to the music, which would be determined by its own chance procedure.

As someone who likes to plan and prepare, this concept is

mind-boggling and maybe slightly terrifying.

However, as someone who has had the opportunity to experience

performances structured by this method, I find it an amazing opportunity to

create great art.

Perspective

Cunningham discarded the conventions of proscenium

orientation. Work could occur on any

part of the stage, oriented in any direction (not necessarily front) at any

point.

Technology

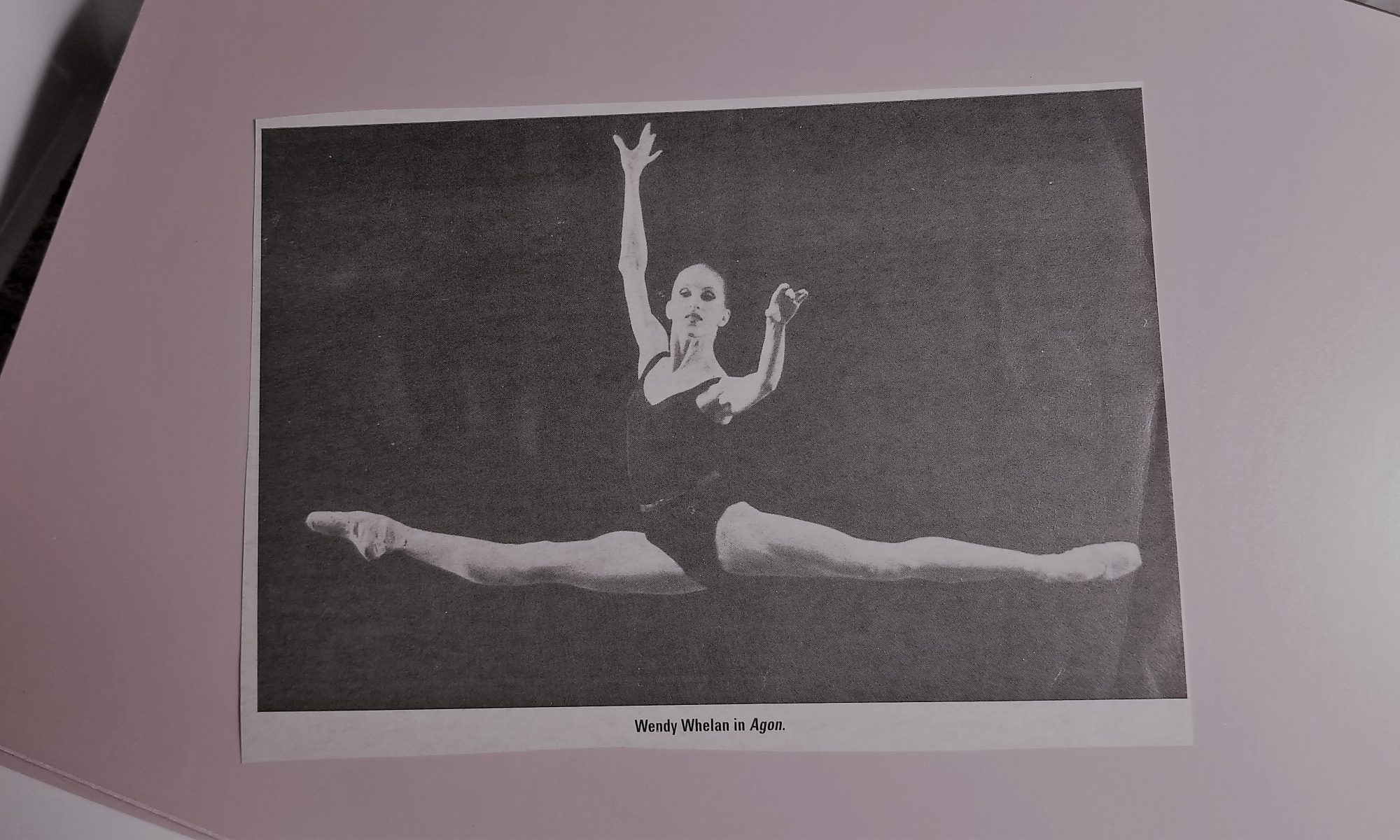

The most long-reaching facet of Cunningham’s work may be his

pioneering use of technology in dance – video in the 1970s and computers beginning

in the 1980s. I believe that one key reason

that he was able to so successfully translate his work to the video medium is his

abandonment of proscenium perspective. Dance

that is oriented to and filmed from an exclusively front-facing perspective tends

to lack dimension to the viewer. By

abandoning this convention, he enabled the camera and by proxy, the viewer, to

become a part of the movement.

He was an early adopted of a computer program, DanceForms which enabled him to create choreography via computer that would later be translated onto living dancers.

Cunningham viewed randomness as a positive, naturally occurring quality. I find his dedication to the concept of chance both contradictory and inspiring. He very consciously committed to developing and cultivating a level of virtuosity that would allow his dancers to execute movement that however randomly generated had begun as a very specific and defined idea. In his work the movement stands alone, it does not represent a narrative or ideas such as emotions. He was very self-consciously trying to avoid imposing his own biases upon his work.

Next week, part II of this post will talk about the exhibit, Merce Cunningham, Clouds and Screens.